The Arts as Buddhist Practice

The talks last night went very well.

Kim Swennes, a harpist, opera singer and thanatologist, played harp as we gathered in.

Jacqueline Mandell was MC - and she organized the event. She is a founding teacher of

Samden Ling "A Sanctuary for Meditative Contemplation."

Tim Tapping, president of the

Northwest Dharma Association talked about the organization, based in Seattle. The organization is unique in North America in its breadth of inclusion of all lineages of Dharma practice.

My talk came first, and as mentioned in the last post amounted to an exposition on the role that Modern and Contemporary Artists have played and continue to play in giving form to the teachings. See below the bibliography on this subject.

Jan Waldman, a long time practitioner gave a talk on Chado, the Way of Tea. Jan was deeply trained in Japan and the US, and has taught and performed tea at Lewis and Clark College and elsewhere for decades.

Next was

Prajwal Vajracharya, of

Dance Mandal. Prajwal and his student gave a beautiful demonstration of Himalayan Buddhist ritual dance.

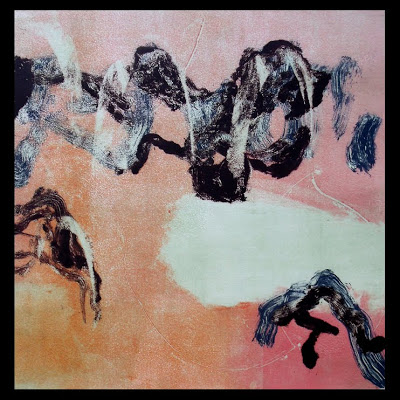

white tara by Sanje

Then came

Sanje Elliott offering insight on Motivation in practice, both of Dharma practice and Art practice. Sanje is an accomplished

Thangka painter and teaches thangka painting here in Portland. He demonstrated the initial drawing of a Buddha head following the traditional form built on a thigse or diagram. Kim accompanied on the harp as he drew.

Lisa Stanley is a teacher in the

Shambhala tradition and a student of

Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche. She gave an interesting talk on Ikebana, including insights from Trungpa, who practiced in the Sogetsu school of Ikebana. This school is known as the non-conformist flower artist school. Some of their arrangements can be wild.

(My mother, Margaret Keenan (Gunn) Lacey, was a practitioner in this school. I watched her over the years become an artist. She knew every flowering bush or tree in her area. "Oh, Jeffrey! Let's go through the arboretum to see if that azalea is blooming!" She once had to be rescued by the fire department. At about 79 years old, she had climbed into an apple tree on the edge of the property. She fell and could not get up. She was over the berm from the parking lot of her condo, and no one could hear her cries over the noise of the street far below. But someone saw her from the other condos way across the street. He called the Fire Dept. and they came for her. They left flowering apple branches on her car. She later brought an apple pie down to the Station. Art requires great sacrifice and humility.)

Lastly,

Kim Swennes, the harpist, talked about

Thanatology, the self effacing practice of calming the dying through gentle (not vague!) music for their final transition from this life. This was a really fine talk, and pertinent for me as my dad just this week escaped the kiss of death. His time is near, but I will have a chance to see him one more time. Death is the ultimate meditation, according to the Buddha:

Of all footprints,

that of the elephant is supreme.

Of all mindfulness meditations,

that on death is supreme.

(from Sogyal Rinpoche's

The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, p. 26)

I will continue presenting out takes from my talk over the coming weeks. Here below is the bibliography for those who like to read up on these things.

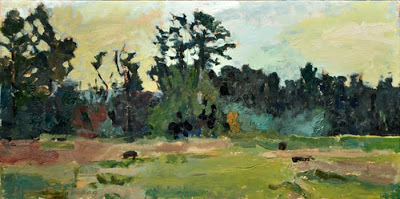

Tarawaya Sotatsu - Waves at Matsushima - 16th c

Bibliography – The Arts as Buddhist Practice

Abram, David. 1996. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More than Human World. New York: Vintage Books, Random House.

Baas,

Jacqueline. 2005. Smile of the Buddha:

Eastern Philosophy and Western Art

from Monet to Today. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California

Press.

Baas,

Jacqueline and Mary Jane Jacob. 2004. Buddha

Mind in Contemporary Art.

Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press.

Berger,

John. 1986. The Sense of Sight. New

York: Pantheon Books.

2001.

The Shape of a Pocket. New York:

Vintage Books, Random House

2007.

Hold Everything Dear: Dispatches on

Survival and Resistance.

New

York: Pantheon Books.

Binyon,

Laurence. 1911. The Flight of the Dragon:

An Essay on the theory and Practice

of Art in China and Japan. London: John Murray

1959.Painting in the Far East: An Introduction to

the History of Pictorial Art

in

Asia Especially China and Japan. New

York: Dover Publications, Inc.

Catoir,

Barbara. 1991. Conversations with Antoni

Tàpies. Munich: Prestel- Verlag.

Crane,

George. 2000. Bones of the Master: A

Journey to Secret Mongolia.

New York: Bantam Books

Coomaraswamy,

Ananda K.1956. Christian and Oriental

Philosophy of Art. First published

1937 as Why Exhibit Works of Art? New

York: Dover Publications.

1956. The Transformation of Nature in Art. First published 1934.

New

York: Dover Publications.

Dufwa,

Jacques. 1981. Winds from the East: A

Study of Manet, Degas, Monet and

Whistler 1856-86. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International.

Ecke,

Tseng Yu-ho. 1988. Wen Jen Hua: Chinese

Literati Painting from the Collection

of Mr. and Mrs. Mitchell Hutchinson. Honolulu: Honolulu Academy

of Arts.

Some Elements of Modern Art in Classical

Chinese Painting. Honolulu: University

of Hawai’i Press.

Fischer,

Felice. 2003. Mountain Dreams:

Contemporary Ceramics by Yoon Kwang-cho.

Philadelhia: Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Heine,

Stephen. 1997. The Zen Poetry of Dogen:

Verses from the Mountain of Universal

Peace. North Clarendon, Vermont: Tuttle Publishing.

Hinton,

David. 2006. trans. The Selected Poems of

Wang Wei. New York: New Directions

Books.

Hisamatsu,

Shin’ichi. 1971. Gishin Tokiwa, trans. Zen

and the Fine Arts. Tokyo: Kodansha International

Holmes,

Stewart W. and Chimyo Horioka. 1973. Zen

Art for Meditation. Rutland,

Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Co.

Klee,

Paul. 1948. On Modern Art. Introduction

by Herbert Read. London: Faber and

Faber.

La Plante,

John D. 1992. Asian Art. 3rd

Ed. Boston: McGraw Hill

Larson,

Kay. 2012. Where the Heart Beats: John

Cage, Zen Buddhism, and the Inner

Life of Artists. New York: The Penguin Press.

Linroth,

Rob. 2004. Paradise and Plumage: Chinese

Connections in Tibetan Arhat

Painting. New York: Rubin Museum of Art.

Lipsey,

Roger. 1988. An Art of Our Own: The

Spiritual in Twentieth Century Art.

Boston & Shaftsbury: Shambhala

Publications, Inc.

Little,

Stephen. 1991. Visions of the Dharma:

Japanese Buddhist Paintings and Prints

in the Honolulu Academy of Arts. Honolulu: Honolulu Academy of Arts.

Loori,

John Daido. 2005. The Zen of Creativity:

Cultivating your Artistic Life.

New

York: Ballantine Books and Dharma Communications.

Maezumi,

Hakuyu Taizan. Photographs by John Daido Loori. The Way of Everyday

Life: Zen Master Dogen’s Genjokoan with Commentary. Zen Writing

series; 5. 1978. Los Angeles: Center Publications.

Nakamura,

Tanio. 1957. Sesshu Toyo. English

text by Elise Grilli. Rutland, Vermont:

Charles E.

Tuttle Co.

Okakura,

Kakuzo. 1956. The Book of Tea.

Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Co.

Pine,

Red. 2000. The Collected Songs of Cold

Mountain. Port Townsend: Copper Canyon

Press.

Poshyananda,

Apinan. 2003. Montien Boonma: Temple of

the Mind. London: Asia

Society, Asian Ink.

Rose,

Barbara Stella. 1975. Art as Art: The

Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt.

Berkeley,

Los Angeles and London: University of California Press.

Sirén,

Osvald. 1963. The Chinese on the Art of

Painting. New York: Schocken

Books.

Sullivan,

Michael. 1979. Symbols of Eternity: The

Art of Landscape Painting in China.

Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Suzuki,

Shunryu. 1999. Branching Streams Flow in

the Darkness: Zen Talks on the

Sandokai. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press.

Trungpa,

Chogyam. 1996. Dharma Art. Judith Lief,

ed. Boston & London: Shambhala.

Tseng

Yu-ho. 1963. Some Contemporary Elements

in Classical Chinese Art. Honolulu:

University of Hawaii Press.

van Briessen,

Fritz. 1962. The Way of the Brush:

Painting Techniques of China and

Japan. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Co.

Watson,

Burton. 1994. Selected Poems of Su Tung-p’o. Port Townsend, Washington: Copper

Canyon Press.

Yanagi,

Soetsu. 1972. The Unkown Craftsman: A

Japanese Insight into Beauty.

Tokyo: Kodansha International.